I met Michael that evening in 1997 in ‘The Red Lion’ in Piccadilly because he was having a drink with Don Paterson who had been my teacher at the Arvon Foundation I was very pleased to see Don. At the time Donaghy and Paterson were the two most well known young poets of their day. I think Don had just published his second great collection: ‘God’s Gift to Women’ and it’s worth reading its great poem, ‘A Private Bottling’ because it’s the great heartbreak poem of the 90’s. Don had taught ten of us for a week in a little house in the wilds of Scotland. ‘More people write poetry in England than read it,’ was the first thing he said to us. He was not happy about it. On the last night we read poems by other poets that inspired us and he had let me read the whole of ‘The Lady of Shallot’ out loud – it’s over twenty stanzas long. This is the kind of thing a young poet remembers- how much poetry ‘territory’ she is allowed to occupy in public.

I must have said something interesting that engaged Michael. I nervously wrote his number down on my hand with what ink I had to hand. When was the last time you sucked the nib of a Bic biro in a pub?! Even though we were all very competitive we rarely had paper or working pens on us and you might not be able to find that person from the pub again. There was no Facebook, no internet, no one really had mobiles. It was all going on in our heads. We had our own minds our own thoughts and no Palo Alto interlocutors. We swapped numbers and wrote scraps of possible poems on whatever surface we had to hand, bits of paper, beer mats, even our own flesh (sometimes other peoples.) Sometimes the phone number was just part of the poetry- It didn’t mean you had to call. Life to a poet was a kind of chaos that would be drawn and withdrawn when you got back to the notebook. Providence was the keyword. ‘Poetry should surprise by a fine excess and not by singularity, it should strike the reader as a wording of his own highest thoughts and appear almost a remembrance.’ as our great man Keats says. Connection was something inky in the 90’s, it only really stretched to meeting people in pubs or at parties and you were only really living in the moment for the sake of some unplanned future. In the pub with the published poets we could create poetry fantasies as if they would last us and they did. And the beer was cheaper. We were usually in the pub because we were on our way back from a poetry reading, we loved listening to each others poetry. I’m sure the pubs had something to do with it. They wrote us poets out like ink. ‘The Red Lion’ in St James.’ I remember like it was yesterday. And it’s still there, replete with engraved glass and mahogany, a jewel box in the ‘rough’ of memory.

However ethereal our scrawlings were, sometimes a phone number felt like something you wanted to hold on to and if it was written on your hand, you would remember not to hold it under at tap until you got back home. Read the poems ‘Black Ice and Rain’ or ‘Machines’ (see below) and you’ll understand why Michael was someone you wanted to hold onto in whatever form you could. We all wanted to have a ‘voice’ that was ‘relevant’, ‘contemporary’, but only a handful of those published in the poetry magazines were ‘the next big thing’ and would go on to be published by one of the ‘big four’. Faber, Picador, Carcanet, Cape, were like the priesthood. I remember going to the TS Eliot awards prize giving at the Shaw Theatre the winners would perform their winning poems. We all wanted to be up there.

Michael would often stay for three or four pints in the pub near City University with his students after his poetry course like he was simultaneously sitting in state and in the clearing of an ancient forest. He would give the assembled novices their real poetry lesson: ‘I can’t really teach you anything: It is something you learn from the greats who had left the building, just read their work, go back to the page, form your bonds that way’ he would say,

‘Want to come and hear me read in Acton?’ He said a week later. We can go together, it’s quite far but we can have a pint when we get back into London.’ Ironically, I remember the tube journey, not the pint. Going to Acton on the tube in rush hour. everyone crammed together like a pub on a Saturday night with no drink. But when Michael stood on the stage in Acton to recite poems from his new collection, I knew that I would have travelled barefoot along the train lines to hear him.

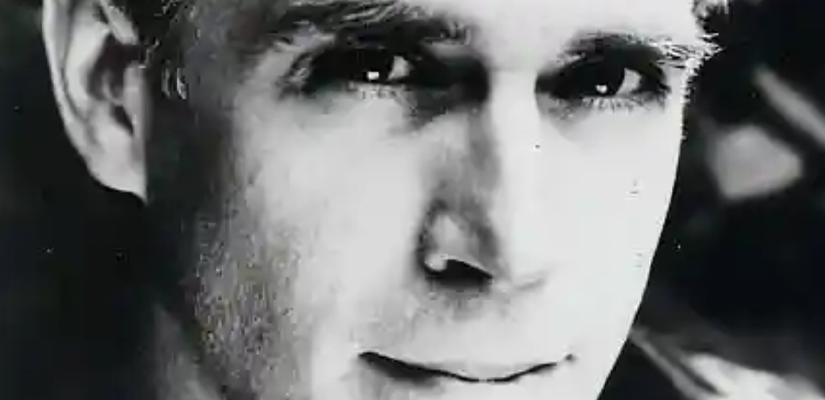

Twelve years ago, Michael died suddenly of a brain haemorrhage, I’m sure many would agree it was the greatest loss to the London poetry community in 50 years. Don Paterson wrote a great elegy about his friend: ‘Ghost’. It is a thing to have known two great poets who wrote about each other. One always hopes that a great poet thinks that your talent is worth nurturing. But it was enough to be there. He didn’t learn phone numbers, but he learned his own poems- by heart. Reciting them as if they were old Irish ballads, the words and feelings the poems brought to his mouth looked you straight in the eye.

I think I only showed him one of my poems ‘Spectacle’. I suppose I didn’t think the others were worthy. He called it a ‘clever little machine’. I hold this close, it reminds me that poetry is not the territory of sentimentality. I think he would be glad I had decided to teach the great poets. And I recommend his Collected Poems to my students as a primary text, because he is one of the greats who will leap from the page to give you his bond. Here, give this one a try. Take a few minutes to mediate on its knowingness. Learn a few lines by heart…study the technique. It will change how your week goes… especially if you ride a bike…

‘Machines’ by Michael Donaghy. (2000)

Dearest, note how these two are alike:

This harpsichord pavane by Purcell

And the racer’s twelve-speed bike.

The machinery of grace is always simple.

This chrome trapezoid, one wheel connected

To another of concentric gears,

Which Ptolemy dreamt of and Schwinn perfected,

Is gone. The cyclist, not the cycle, steers.

And in the playing, Purcell’s chords are played away.

So, this talk, or touch if I were there,

Should work its effortless gadgetry of love,

Like Dante’s heaven, and melt into the air.

If it doesn’t, of course, I’ve fallen. So much is chance,

So much agility, desire, and feverish care,

As bicyclists and harpsichordists prove

Who only by moving can balance,

Only by balancing move.

Reading Matter:

Shibboleth: Michael Donaghy

God’s Gift to Women: Don Paterson

Rain: Don Paterson

Venue:

The Red Lion. St James’ Square/